This book is a fascinating read in its own right but it is also an invaluable source for my research into fairy literature that I have been pursuing along with Sam as part of the OGOM Project. This is a continuation of work that inspired our ‘Ill met by moonlight’ conference in 2021, which led in turn to our forthcoming edited collection, Gothic Encounters with Enchantment and the Faerie Realm in Literature and Culture: ‘Ill met by moonlight’).

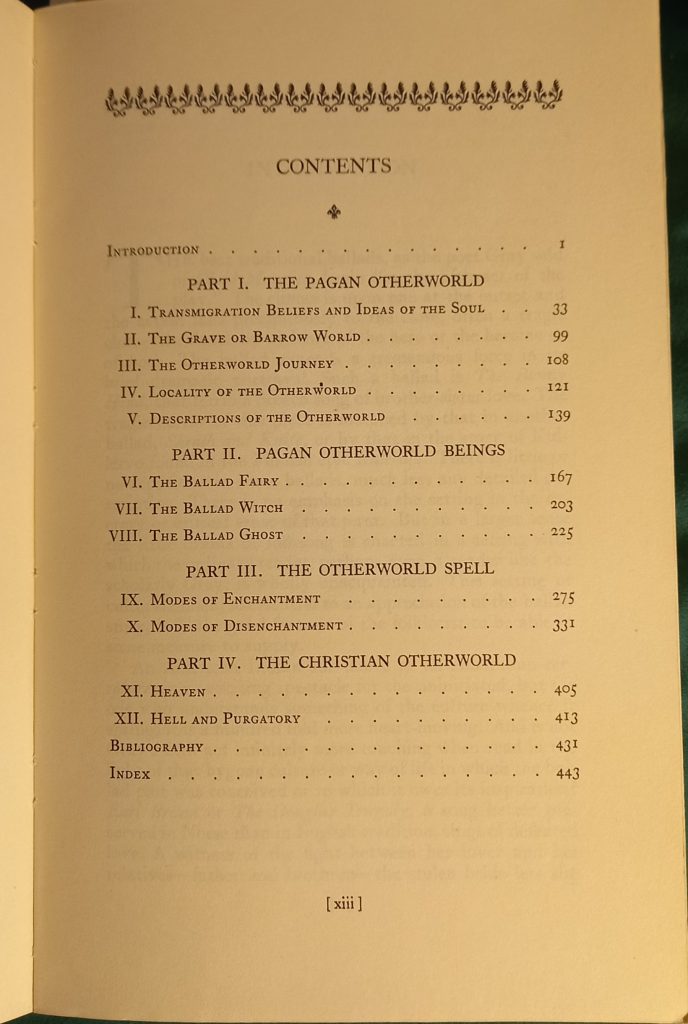

The contents list alone is inspiring!

Wimberley explores the vast corpus of ballads and their variants, identifying the folkloric elements manifest there or more covertly suggested. All the themes that fascinate us at OGOM are here: fairies and elves, mermaids, witches, and ghosts; enchanted food, music, and dance; fairy gifts; the fairy kiss; fairy and demon lovers; changelings; the Otherworld; human/animal metamorphoses; sacred groves.

The dangerous seductions of fairy food, music, and dance are dwelt on in detail; these motifs, for me, are a fruitful starting point for explorations of enchantment and utopianism, ideas which I am writing about in my chapter ‘Fairy carnival: Music, dance and food in the re-enchantment of modernity from Hope Mirrlees’s Lud-in-the-Mist to dark fairy romance’, which will appear in the above mentioned book.

There is an extended section on the ballad ‘Tam Lin’ and the miraculous transformations the hero undergoes before he is released from the Queen of Faerie. This is one of the finest of the ballads and an important example of the Demon Lover theme which informs dark fairy romance through to contemporary paranormal romance (and is another of OGOM’s research areas).

The important chapter on fairies has a significant section on their stature – a topic that is frequently raised in discussions of these creatures. The conclusion is that the authentic fairy is rarely diminutive, appearing so only when exercising their shape-shifting abilities.

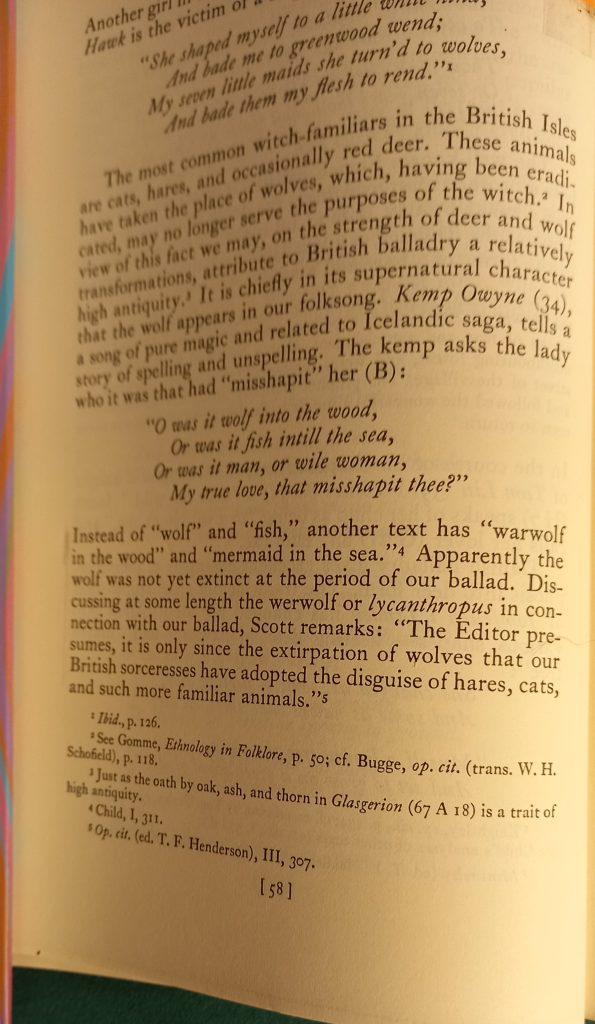

Wimberley even discusses a link between mermaids and werewolves, recalling past and future OGOM conferences:

The book is full of detail, tracing a vast amount of folkloric images and plot motifs through the ballads, meticulously examining their variants and the relationship between each other, and, now and then, with continental ballads such as those from Scandinavia. Wimberley also draws out (showing a very partial sympathy with the pagan!) how the earlier pagan elements often become overlain and sometimes softened by Christian belief.

Wimberley’s thesis, however, is dominated by a very reductive universalism that aims to uncover common sources in the religious mentality of ‘primitive’ peoples from around the world. It rests on an ethnology which would be much disputed by contemporary scholars (it was published in 1928). That aside, this is a rich resource for those who want to explore the magical, eerie, often very dark aspects of the Otherworld, Faerie, and other supernatural features of the traditional ballad.

Lowry Charles Wimberley, Folklore in the English and Scottish Ballads (1928; New York: Dover Publications, 1965)