‘Some curious disquiet’: Polidori, the Byronic vampire, and its progeny

A symposium for the bicentenary of The Vampyre 6-7 April 2019, Keats House, Hampstead

Fees: £70/day waged; £40/day postgraduate and unwaged

Fee includes all the talks, bespoke catering, including lunch and vampyre cup cakes, tour of Keats House and excursion to Highgate Cemetery.

*** Programme here; abstracts here.

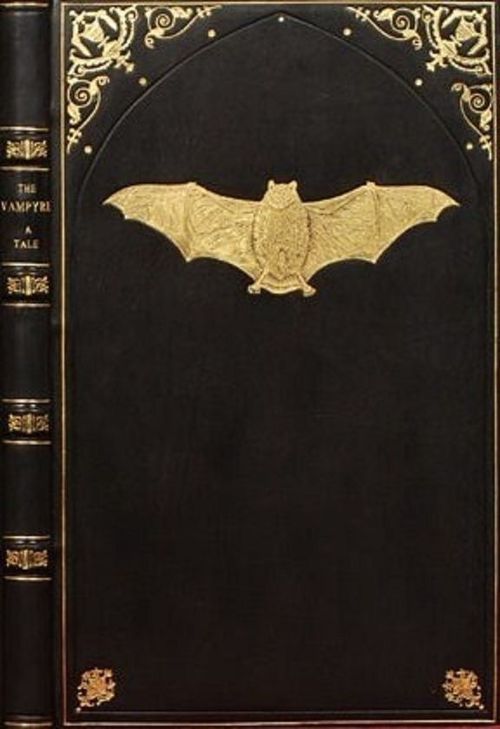

John Polidori published his tale The Vampyre in 1819. It is well known that his vampire emerged out of the same storytelling contest at the Villa Diodati in 1816 that gave birth to that other archetype of the Gothic heritage, Frankenstein’s monster. Present at this gathering were Polidori (who was Byron’s physician), Mary Godwin, Frankenstein’s author; Claire Clairmont, Percy Shelley, and (crucially) Lord Byron.

Byron’s contribution to the contest was an inconclusive fragment about a mysterious man characterised by ‘a curious disquiet’. Polidori took this fragment and turned it into the tale of the vampire Lord Ruthven, preying on the vulnerable women of society. The Vampyre was something of a sensation (partially owing to its misattribution to Byron) and spawned stage versions and imitations that were hugely popular.

Sir Christopher Frayling declares The Vampyre to be ‘the first story successfully to fuse the disparate elements of vampirism into a coherent literary genre’. This could be qualified; if short political satires and ethnographical enquiries featuring the monster constitute genres, then these had already emerged out of folkloric accounts during the eighteenth century. But Polidori gave the creature the form that largely persists through subsequent vampire narratives, transforming it from the animalistic monster of the Slavic peasantry to something that can haunt the drawing rooms of Western society, undetected. Polidori’s Lord Ruthven, modelled on Lord Byron via Lady Caroline Lamb’s scandalous Glenarvon (1818), is aristocratic and sexualised and, though something of a blank canvas, even potentially sympathetic, providing a template for the ‘Byronic hero’ that features in Gothic romance down to the paranormal romances of the present day. Thus, the familiar vampires Count Dracula (1897), Anne Rice’s Lestat (1976), and the infamously sparkly Edward Cullen of Twilight (2005) can all claim to have been his heir.

This symposium will trace Polidori’s bloodsucking progeny and his heritage of ‘curious disquiet’ in literature and other media. It is a return to the beginnings of the Open Graves, Open Minds Project, which began with a very successful conference on vampires in 2010 followed by an edited collection, Open Graves, Open Minds: Representations of Vampires and the Undead from the Enlightenment to the Present Day, ed. by Sam George and Bill Hughes (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013) and the first special issue of Gothic Studies devoted to vampires (May 2013).

Guest speakers have been invited to share their research into the many variations on monstrosity and deadly allure spawned by Polidori’s seminal textual reincarnation of Byronic glamour. The delegates have been selected for their expertise in the Byronic, the Gothic, and the vampiric. The speakers are: Sir Christopher Frayling, Prof. Catherine Spooner, Prof. William Hughes, Dr Stacey Abbott, Dr Sue Chaplin, Dr Xavier Aldana Reyes, Dr Sorcha Ní Fhlainn, Prof. Nick Groom, Prof. Gina Wisker, Dr Sam George, Dr Bill Hughes, Dr Ivan Phillips, writer Marcus Sedgwick, and OGOM ECRs and doctoral students Dr Kaja Franck, Daisy Butcher, and Dr Jillian Wingfield.

When from this wreathed tomb shall I awake!

When move in a sweet body fit for life,

And love, and pleasure, and the ruddy strife

Of hearts and lips!

(John Keats, Lamia (1820))

The Symposium is being held at the beautiful Keats House, Hampstead (where OGOM held a symposium for Bram Stoker’s centenary in 2012). Keats House is where the poet John Keats lived from 1818 to 1820, and is the setting that inspired some of Keats’s most memorable poetry. Here, Keats wrote ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, and fell in love with Fanny Brawne, the girl next door. It was from this house that he travelled to Rome, where he died of tuberculosis aged just 25. Keats created one incarnation of the vampire in his Lamia (1820).

The event will include a tour of Keats House (who hold a first edition of The Vampyre) and a trip to Highgate Cemetery, home of the Highgate Vampire (a sensation of the 1970s), and where Karl Marx (who made good use of the vampire metaphor) and Lizzie Siddal lie. Lizzie wrote poetry and is known as the muse of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. He famously buried his poems with her when she died from laudanum poisoning in 1862. He later exhumed her grave and she was said to have not decomposed, that her beautiful auburn hair had not faded. This story has been linked to the description of the vampire Lucy in her coffin in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897). Tim Powers‘s 2012 novel Hide Me Among the Graves claims that Rossetti exhumed her not to recover his poems but to defeat a vampire, her husband’s uncle, John Polidori! Douglas Adams, Christina Rossetti, and other luminaries also lie in the cemetery, in peace (we hope).

We are very grateful for the cooperation of Keats House and for generous grants towards the Symposium from the British Association for Romantic Studies, the International Gothic Association, and the University of Hertfordshire.