In April of 1819, a London periodical, the New Monthly Magazine, published The Vampyre: A Tale by Lord Byron. Notice of its publication quickly appeared in papers in the United States.

Byron was at the time enjoying remarkable popularity and this new tale, supposedly by the famous poet, caused a sensation as did its reprintings in Boston’s Atheneum (15 June) and Baltimore’s Robinson’s Magazine (26 June).

The Vampyre did away with the East European peasant vampire of old. It took this monster out of the forests, gave him an aristocratic lineage and placed him into the drawing rooms of Romantic-era England. It was the first sustained fictional treatment of the vampire and completely recast the folklore and mythology on which it drew.

By July, Byron’s denial of authorship was being reported and by August the true author was discovered, John Polidori.

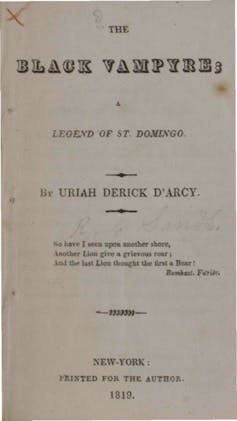

In the meantime, an American response, The Black Vampyre: A Legend of St. Domingo, by one Uriah Derick D’Arcy, appeared. D’Arcy explicitly parodies The Vampyre and even suggests that Lord Ruthven, Polidori’s British vampire aristocrat, had his origins in the Carribean. A later reprinting in 1845 attributed The Black Vampyre to a Robert C Sands; however, many believe the author was more likely a Richard Varick Dey (1801–1837), a near anagram of the named author.

What is so remarkable about this story is that it is an anti-slavery narrative from the early 1800s which also contains America’s first vampire who is Black. It is also perhaps the first short story to advocate the emancipation of slaves, released 14 years before Lydia Child published An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans, which is widely considered the first anti-slavery book.

Surprisingly, this ground-breaking text is relatively unknown, even in Gothic circles. It appears in none of the seminal histories of the vampire, for example, and is not included in any of the classic and recent collections of vampire short fiction. There is one online edition, a labour of love, excellently prepared, to enable the teaching of the text by the Americans, Ed White and Duncan Faherty.

A mixed union

The Black Vampyre also explores the idea of mixed marriage at a time when interracial love was deemed taboo.

Darcy’s narrative begins with a slave-owner Mr Personne, in what is now Haiti repeatedly trying to kill a 10-year-old slave. As much as he tries though the corpse keeps reviving. Personne orders the child to be burned but the boy moves with supernatural speed and miraculously causes the slave-owner to be flung into the fire instead. Before Mr Personne dies, his wife informs him that the cradle of their unbaptised son is empty apart from his skin, bones, and nails.

Some years later we return to Personne’s widow, Euphemia, who is in mourning for her third husband. She is visited by two strangers, an extremely handsome Black man, dressed as a Moorish prince, accompanied by a pale European boy. He charms her with his elegance and beauty and rapidly wins her hand in marriage, which takes place that evening. That same night he reveals that he is a vampire and converts Euphemia to his bloodthirsty set.

Monsters aside, Published in 1819, an interracial marriage would have made for shocking reading – not to mention between a former slave and his one-time mistress.

Vampirish children

Married to a monster and now a monster herself (in the eyes of society too), Euphemia learns that the prince’s pale young companion is her vanished son – now also a vampire. The prince gives the boy named Zemba back to Euphemia along with her first husband’s money so they can escape to Europe.

On their way, they find themselves in a cavern with a group of noble-looking vampires and a crowd of slaves. The prince addresses the crowd in the language of revolutionary Enlightenment:

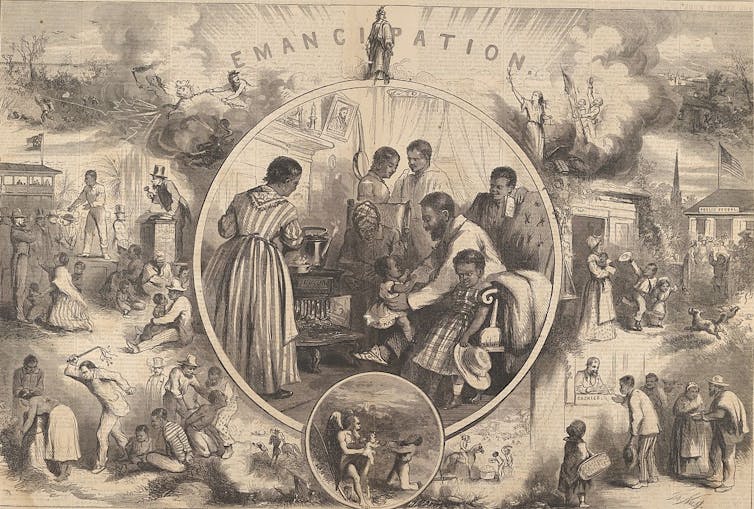

Our fetters discarded, and our chains dissolved, we shall stand liberated, – redeemed, – emancipated, – and disenthralled by the irresistible genius of UNIVERSAL EMANCIPATION!!

This draws on the then recent Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), which ended slavery and French control of the colony. The vampires, like the slaves, are forced to exist on the fringes of society and so are rebelling against their lot in life. However, unlike Haiti’s, the rebellion is thwarted by a group of soldiers and the vampires are staked to death.

Luckily Euphemia and Zemba escape, sipping a potion that can restore a vampire to the human state. They go on to lead a happy family life, Zemba is finally baptised as Barabbas and life goes on. That is until Euphemia gives birth to a mixed-race son (presumably the prince’s) with “vampirish propensities”. This is the first instance of a mixed-race vampire ever recorded in literature.

Important for being the first American vampire text and for depicting the first Black vampire in literature, The Black Vampyre has a contemporary resonance. The racism cultivated by slavery lives on; the struggle against it and the dreams of universal humanity expressed in the Haitian Revolution continues. The links The Black Vampyre makes between racial oppression and a vampiric society, though ambivalent, make its resurrection worthwhile. The crude goriness and spookiness of Gothic vampire narratives can still have an ethical force.![]()

Sam George, Associate Professor of Research, University of Hertfordshire

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.