Kaja and Sam have made me feel guilty, so I’ll just give an account of what I’ll be talking about at the Being Human: Redeeming the Wolf event.

I’ll be following up some of the themes that Sam and Kaja have talked about but—I must confess—I’m being something of a wolf in sheep’s clothing here. For I’ll be talking more about redeeming the human more than redeeming the wolf. Kaja has talked about the antiquity of stories of transformation into wolf, of their diversity, and of how the actual wolf may have been suppressed by understanding these stories as parables of what it is to be human. Sam likewise has tried to redeem the wolf by looking at accounts of wild children nursed into humanity by benevolent wolves.

I begin by talking about storytelling itself. Being human is very much about telling stories. It’s what differentiates us from beasts. Stories posit a future; they point towards a goal. They are one way we work out among ourselves what our values and aspirations are. And, among other things, they allow us to understand the relations between humanity and wilderness, and what we have lost or found in our emergence out of animality.

One exemplary story in this respect is, of course, ‘Red Riding Hood’, a fairy tale which also has the werewolf motif latent within it. Here, the wolf can figure as the bestial side of humanity; importantly, sexuality is at play here as much as the violence and cunning that other wolf narratives depict. This is brought out in the multifarious variations on the tale since the classic versions of Grimm and Perrault—in Angela Carter’s wolf tales, for instance, or in numerous more frivolous retellings in popular culture.

One exemplary story in this respect is, of course, ‘Red Riding Hood’, a fairy tale which also has the werewolf motif latent within it. Here, the wolf can figure as the bestial side of humanity; importantly, sexuality is at play here as much as the violence and cunning that other wolf narratives depict. This is brought out in the multifarious variations on the tale since the classic versions of Grimm and Perrault—in Angela Carter’s wolf tales, for instance, or in numerous more frivolous retellings in popular culture.

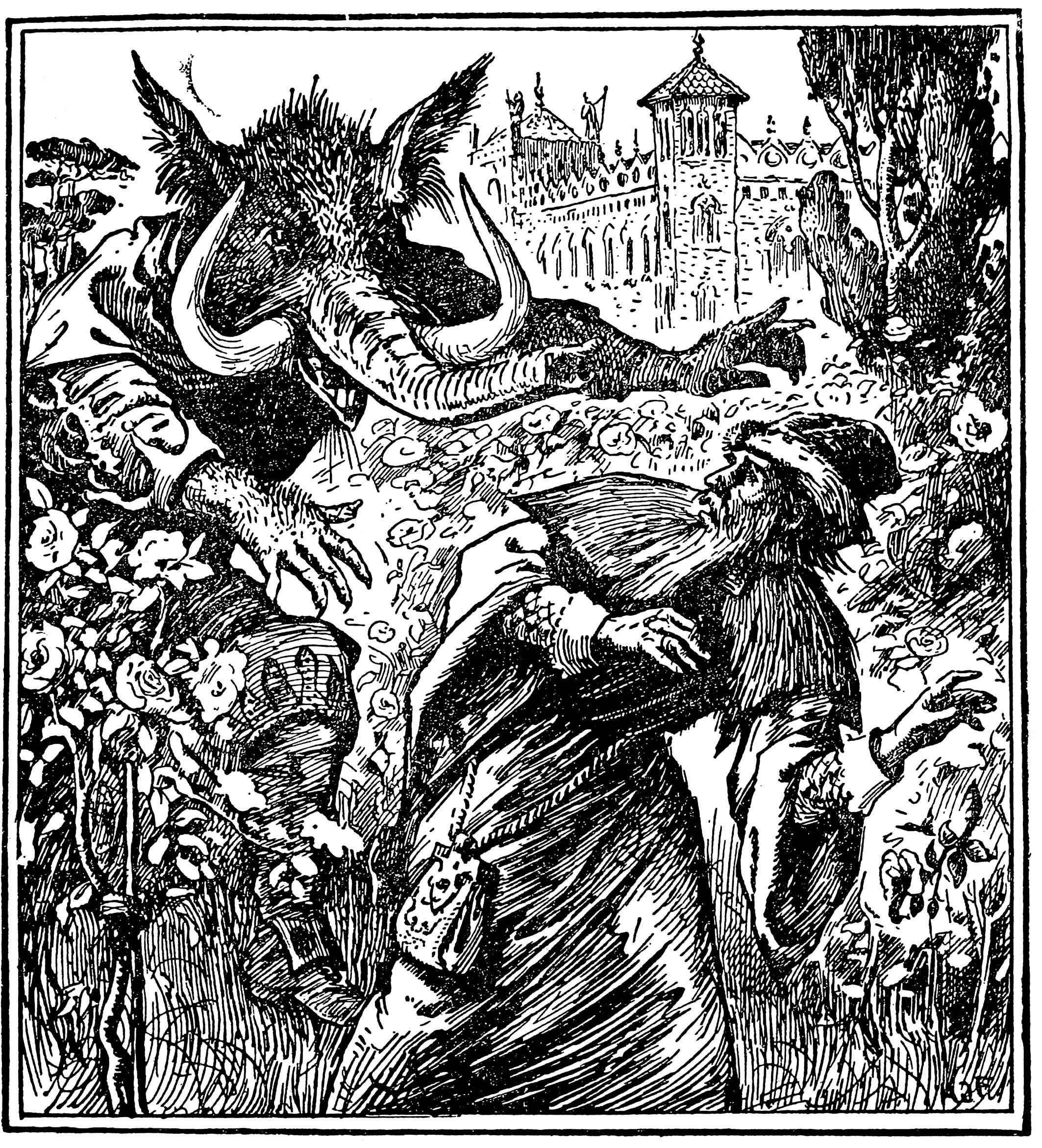

I make a slight detour to consider another classic fairy tale, one which lies at the roots of the research I’ve been doing on the genre of paranormal romance: ‘Beauty and the Beast’. The Beast here is not a wolf, and he’s not described as lupine in the original story; different illustrators portray him in different ways, often leonine. Iona and Peter Opie claim that ‘Beauty and the Beast’ is ‘The most symbolic of the fairy tales after Cinderella, and the most intellectually satisfying’. Perhaps the tale lends itself more easily to allegory than most; you have the polarised qualities of hero and heroine; the abstraction of a spiritual quality, ‘Beauty’, set against the earthiness of ‘Beast’. There are hundreds of variations, adaptations, and reworkings of the basic story alone. But the theme of human and monstrous lovers also lies behind the recently emerged genre of paranormal romance.

I make a slight detour to consider another classic fairy tale, one which lies at the roots of the research I’ve been doing on the genre of paranormal romance: ‘Beauty and the Beast’. The Beast here is not a wolf, and he’s not described as lupine in the original story; different illustrators portray him in different ways, often leonine. Iona and Peter Opie claim that ‘Beauty and the Beast’ is ‘The most symbolic of the fairy tales after Cinderella, and the most intellectually satisfying’. Perhaps the tale lends itself more easily to allegory than most; you have the polarised qualities of hero and heroine; the abstraction of a spiritual quality, ‘Beauty’, set against the earthiness of ‘Beast’. There are hundreds of variations, adaptations, and reworkings of the basic story alone. But the theme of human and monstrous lovers also lies behind the recently emerged genre of paranormal romance.

The most familiar example of paranormal romance must be Stephenie Meyer’s best-selling Twilight (2005). A collision or mating of genres has taken place, and this is important for those interested in the forms of storytelling and how kinds of writing emerge and mutate. This new literary form has many of the trappings of Gothic, but the plot is subordinated to the movement towards amatory consummation of romantic fiction; the setting tends to be contemporary; it seems to assume a female readership; and, crucially, it centres on love affairs between humans and supernatural creatures.

But werewolf romances are almost as popular as vampires. Each species of monster lends itself to different domains of enquiry. The shapeshifter, especially the werewolf, is particularly suited as an instrument for exploring the boundaries of humanity and animality, culture and nature. (Kaja has talked about this, and highlighted how the lupine has become suppressed in favour of the human.)

Many contemporary werewolf romances feature the obligatory ‘post-feminist’ feisty female protagonist—she has to be there to conform to the expectations of the romance genre and its largely female audience. Yet contradictions emerge: you have this independent woman but these books also show how, as werewolves, driven by animal instincts, the heroines submit both to pack hierarchy and to the dominant alpha male. The stories allow them to be fierce and strong, and enjoy uninhibited sex—but they tie them to inescapable biological forces at the same time.

And there’s the wolf pack. Werewolves here are seen as social but again that social life is determined inescapably by biology. Aggression and hierarchies of both class and gender are seen as inevitable.

Thus many contemporary werewolf romances not only make wolves look bad, they denigrate humans, too, by binding them to ideas of animality that are fixed and essentialist. Yet it’s only through stories that we can acknowledge our humanity and transcend those ideas of fixedness. I finish by looking at one Young Adult paranormal romance that bucks the trend—Maggie Stiefvater’s Wolves of Mercy Falls series.

Stiefvater overall asserts the distinctively human powers of language, of individual identity, and free will as her characters find their voice and define their projects. The final verdict is that only the possibility of return to humanity makes animality bearable. Yet, even so, this very subtle and fine work allows room for the wolf. Stiefvater represents a humanity uniquely emancipated through language and creates drama out of the Othering of wildness, and yet she suggests that being human rests upon that evanescent animality, hinting at the redemption of both human and wolf.