Nick Lane’s adaptation of Dracula preserves the eerie essence of Bram Stoker’s classic while adding a fresh, contemporary twist. The promotional blurb promises that ‘as a new shadow looms large over England, a small group of young men and women, led by Professor Van Helsing, are plunged into an epic struggle for survival’, and Lane delivers on this atmospheric promise with a gripping performance. The show is recommended for age 12+, which is an accurate rating as the horror is implicit throughout the production. The show is a digestible length at 150 minutes (including the interval).

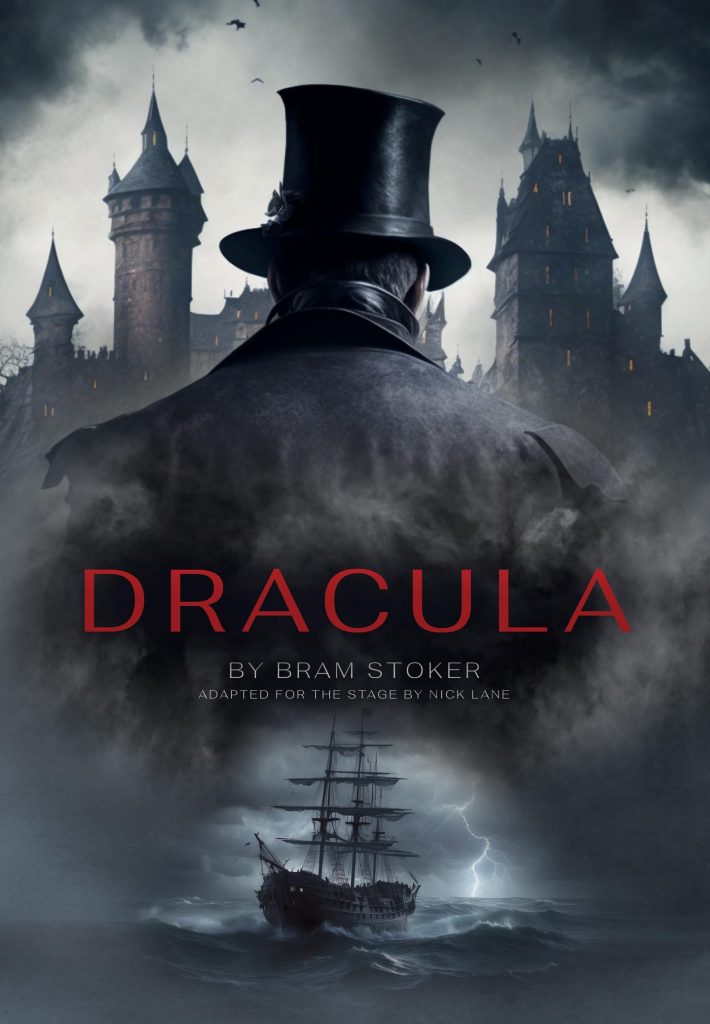

Exactly one hundred years ago, at Derby’s old Grand Theatre, Dracula strode onto the stage for the first time. The venue closed in 1950, so the character outlived his theatrical birthplace. Blackeyed Theatre is on tour with a new version of Dracula to mark the centenary. The theatre group offer a vastly different Count Dracula to Hamilton Deane’s original. Nick Lane offers something new by dispensing with the dinner suit and opera cloak as well as the fangs made famous by Christopher Lee. This production adheres to the standard style of the Blackeyed Theatre, the emphasis being on words instead of action, but it is still imaginative, with a strong and passionate cast.

The play is structured in two acts. Act One unfolds from Jonathan Harker’s perspective, offering a glimpse into the harrowing events as seen through his eyes. Act Two then circles back to the beginning of the story, this time immersing the audience in Renfield’s point of view. Both acts stay true to the epistolary format of Stoker’s novel, maintaining the original structure while providing a fresh narrative lens that adds depth to the characters and the story. Lane’s adaptation strikes a brilliant balance between honouring the classic source material and giving it a dynamic, modern edge. Nick Lane recreates the de-ageing process by having three progressively younger actors playing the Count. This works well to an extent, but it does result in a loss of the fear factor for the Count, as with each character change we are somewhat taken out of the action in having to get used to a new actor playing the Count.

In spite of these shortcomings, there is still much to admire about the production. The six actors (Maya-Nika Bewley, David Chafer, Richard Keightley, Pelé Kelland-Beau, Marie Osman and Harry Rundle) play multiple roles, moving effortlessly from one character to another. They also take it in turns to be narrators as they relate the story through letters, diary entries and newspaper articles. Osman is outstanding with a thrilling display as Lucy Westenra, being transformed from an independent, modern-thinking woman into a possessed vampire whose charms have to be resisted.

It has been said that each era produces the monster it needs. This is very much the case here. Nick Lane’s monster, as a product of social mores, is in many ways similar to Vecna from the Duffer Brothers’ Stranger Things. Apparently, the monster that this generation needs is capable of breaking human bodies just by using mind power. Nick Lane explained in an interview that he ‘wanted to explore the idea that there is a more complex side to the human struggle against vampyrism’. Lane’s production attempts to explain what is happening biologically to the humans after the vampire attacks. Blood is drawn from the neck, but it is an exchange of fluids that takes over the victim’s personality. Since the first vampire attack occurs an hour into the production, the audience is subjected to a long-winded revelation of the human battle against vampirism. To Lane’s credit, he does give Dracula the voice that he lacks in the novel. If you enjoy productions that are politically correct and cast actors of a different gender or skin colour, then this certainly does so. Nick Lane casts a black woman to play both Lucy and Renfield. This is a positive step, but I would argue that Lane would have done better to create entirely fresh characters and consider writing from the vampire’s point of view. I enjoyed the atmospheric nature of the production, but it did feel rather long-winded in the first act. It held my attention admirably, but it could have benefitted from more ‘bite’. It could be described as Dracula for Academics.

(Jane Gill is a doctoral student at the University of Hertfordshire. Her PhD examines the monstrous feminine in nineteenth-century literature from an eco-Gothic perspective.)