My blog posts have been very absent recently (in my defence I am in the final stages of preparing to submit my thesis). However, I took the time to read and enjoy this article, ‘Remus Lupin and the stigmatised illness: why lycanthropy is not a good metaphor for HIV/AIDS’, about Remus Lupin and his ‘furry little problem’.

The idea of using lycanthropy as a metaphor for disability, and the problems that this incurs, is discussed by Kimberley McMahon-Coleman and Roslyn Weaver in Werewolves and Other Shapeshifters in Popular Culture (2012). One of the particular difficulties which they identify is that the werewolf is understood a priori as a monster. Thus, anything that is identified with werewolfism, such as reading lycanthropy as a metaphor for HIV/AIDS, appears to be always, already monstrous in itself. If Lupin is read as someone living with HIV/AIDS, he starts in a position of monstrosity from which he must redeem himself. As the article suggests, given that Lupin is the exception to the rule of lycanthropy – the ‘good’ werewolf, the novels are in danger of suggesting that it is the victim of societal stigma who must strive to make themselves ‘non-monstrous’. This puts the onus of the individual rather than society and strays into the realm of victim-blaming. Clearly, it should be human society that moves away from the tendency to stigmatise difference.

The idea of using lycanthropy as a metaphor for disability, and the problems that this incurs, is discussed by Kimberley McMahon-Coleman and Roslyn Weaver in Werewolves and Other Shapeshifters in Popular Culture (2012). One of the particular difficulties which they identify is that the werewolf is understood a priori as a monster. Thus, anything that is identified with werewolfism, such as reading lycanthropy as a metaphor for HIV/AIDS, appears to be always, already monstrous in itself. If Lupin is read as someone living with HIV/AIDS, he starts in a position of monstrosity from which he must redeem himself. As the article suggests, given that Lupin is the exception to the rule of lycanthropy – the ‘good’ werewolf, the novels are in danger of suggesting that it is the victim of societal stigma who must strive to make themselves ‘non-monstrous’. This puts the onus of the individual rather than society and strays into the realm of victim-blaming. Clearly, it should be human society that moves away from the tendency to stigmatise difference.

I would suggest that in order to prevent the problematic elements of reading lycanthropy as HIV/AIDS, and perhaps lending this metaphor further weight, the werewolf should have been redeemed – by this I mean changing the definition of the werewolf. The description of the werewolf in Fantastic Beasts & Where to Find Them (2001) states that ‘at the full moon, the otherwise sane and normal wizard or Muggle afflicted transforms into a murderous beast’ (p. 42). This stereotype of the werewolf as losing all sense of self when transformed has become part of popular culture since the twentieth century, particularly in horror films. According to this description, the werewolf IS dangerous, despite the sympathetic presentation of Lupin. Even allowing for the Wolfsbane potion, which itself only a recent addition to Harry Potter werewolf lore, having a werewolf living in close quarters with humans would seem unwise.

Instead, I think that presenting the werewolf as less dangerous would have enabled a more powerful exploration of the effects of societal stigma. The monstrous werewolf of popular culture could be presented as a misconception, which had come about because of the terrifying nature of transforming from one state to another, rather than the inherent danger of the transformed human. The perception of the werewolf as evil could then be deconstructed showing that the werewolf, whether transformed or not, is not dangerous. In this way, being a werewolf would then no longer be monstrous. The texts could suggest that the werewolf has been appropriated as a monster, in order to make a statement about the role of the ‘other’ within society. A character such as Fenrir Greyback, the most extreme presentation of lycanthropy within in the Harry Potter novels, would then be the product of stigmatisation. He takes on the role of the stereotypical werewolf because that is the role that is forced on him by society. In this way the danger of misinformation that has surrounded HIV/AIDS and the risk it poses could be more effectively framed. (I admit even these changes wouldn’t render it a perfect metaphor).

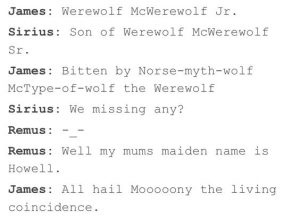

Considering the issue of Remus Lupin and lycanthropy, it is with a heaviness of heart that I state that, though I love the Harry Potter novels and they are a constant companion, Rowling’s writing sometimes falls down on close inspection. The use of lycanthropy as a metaphor for HIV/AIDS appears to be well-intended but is, ultimately, problematic. (In the same way, the lack of democracy in the Ministry of Magic always concerns me). Thus, as the above image shows, Rowling use of names, and research into historical magic, is thrilling and delightful. But the interpretation of the character of Lupin is, perhaps, done more effectively my the readers themselves. Unfortunately Pottermore, whilst a powerful tool for the fandom, has the tendency to curtail the subtle and thoughtful world-building done by the fans of the series. The navigation of the rights of the author and the reader to the text is exemplified in the Harry Potter series. The fandom, often in the form of fanfiction, has constructed powerful narratives regarding the world of Harry Potter, including back stories for many lesser characters, and alternative timelines. These often allow the voices of minority groups to be heard against the predominantly normative space that the novels create. Each clarification by Rowling minimises these voices and denies the role of reader in constructing and re-constructing the textual world. Instead, she offers the definitive reading of characters and situations without acknowledging that the best literature has a multiplicity of interpretations.

(NB: On a personal, and rather light-weight note, the other reason I put in the above image is because my partner’s surname is Howells. As I come to the end of dedicated three years of my life to werewolves, it seems apt that I should stumble across this image).

References:

Rowling, J. K., Fantastic Beasts & Where to Find Them (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2001)

‘If Lupin is read as someone living with HIV/AIDS, he starts in a position of monstrosity from which he must redeem himself.’

I, too, am troubled by the tendency to read monstrosity of some kind as code for AIDS/HIV. I think it is more common with Vampires – I was inundated, for example, with an exhausting amount of (painfully sub-standard) articles on how the vampires on Buffy the Vampire Slayer are all a metaphor for AIDS/HIV. Equating disease (or, occasionally disability in some sources) with monstrosity is, I agree, a dangerous and potentially harmful problem.

You said, ‘Instead, I think that presenting the werewolf as less dangerous would have enabled a more powerful exploration of the effects of societal stigma.’ In the cases where a writer would be intentionally making links between AIDS/HIV and lycanthropy, I would agree. However, I don’t think that the metaphor should be applied so readily. I’m not sure the answer is to change the monsters in the text, but, rather, to stop actively slapping on metaphors for AIDS/HIV unless there is more evidence that this is a valid reading.

I do agree when you say ‘The use of lycanthropy as a metaphor for HIV/AIDS appears to be well-intended but is, ultimately, problematic.’ I think, in this particular case, the fault lies not in what is being read, but how it is being read: sometimes a werewolf is just a werewolf. I would add to this ‘the use of monstrosity, in general, as a metaphor for HIV/AIDS appears to be well-intended but is, ultimately, problematic — even damaging to those with HIV/AIDS’. I don’t think it’s necessarily that Rowling falls on close inspection in the case of Lupin and lycanthropy, but rather that Rowling would have never anticipated a reading of lycanthropy as a metaphor of AIDS/HIV in the first place. (Though, I am the first to say that Rowling does certainly fall on close inspection in general).

I also agree that Pottermore can hinder the Potter series. In fact, I have given up on Pottermore. In my opinion, what made Potter work so well in the first place is that it offers a universe with enough detail to make it feel real, but enough free space for fans to interpret and create new elements. I very much agree with your final thought that ‘Each clarification by Rowling minimises these voices and denies the role of reader in constructing and re-constructing the textual world. Instead, she offers the definitive reading of characters and situations without acknowledging that the best literature has a multiplicity of interpretations.’

Thanks for the interesting read!

Great post, Kaja!

Though I’m inclined to argue somewhat along the lines of Sunday’s comment. The problem may be in the reading itself; I’m wary of reading fantastic fiction as allegory, with a one-to-one correspondence between text and world in that way (unless, of course, it’s the Faerie Queen or something!). Lupin’s werewolfism is surely a very underdetermined metaphor for AIDS/HIV; there are far too many aspects which simply don’t fit. (The case for vampires is more convincing, but even then that kind of reading seems to ignore the actual detail and specificity–and social context–of a text in order to squeeze it into a predetermined hypothesis.)

But this connects to your last point about denying the role of the reader. I would argue that interpretation has to involve a complex interaction between reader, the text itself (and the symbolic system it is embedded in)–and the writer. There are dangers in denying the agency of the writer as much as suppressing that of the reader. Intention, unfashionable as it may be to say so, is important. And readers may need to be constrained sometimes–there are surely invalid, unpersuasive readings as well as valid but unexpected ones. Perhaps the solution here is not to write so that the monster as AIDS victim becomes a better metaphor but simply to argue against what can only be described as bad readings? If Rowling had said that she was representing AIDS or if the text significantly bore it out, then the criticisms are valid. But is this really the case here? I think it does writers and literature–and ultimately readers themselves–an injustice to treat texts in such a one-dimensional way.

But that doesn’t rule out plurality in interpretation. This reminds me very strongly of Richardson’s constant rewritings of Pamela and Clarissa–in a similarly dialogic context to Rowling–in response to readers and fans whose readings, he felt, had gone against his intentions. Yet there are undoubtedly things emerging in his texts that have a life of his own.

This is a very interesting discussion Kaja. For the Books of Blood project we have focused on the gothic nature of illness, in particular blood diseases and invisible or self managed illness. How different it would be if the werewolf were a symbol for diabetes or haemophilia, and it was the perception of the monstrous self that was being explored rather than the process of being othered. Aids/HIV as Susan Sontag has shown in ‘Illness as metaphor’ has its own language in the twentieth century much like Consumption in the 19th. If Rowling did intend this surely it is more a comment on coming to terms with the seemingly monstrous elements of unseen illness, rather than the HIV or werewolf body as actually monstrous. Viewed in this way it is about misconception. The body as contested site, its ownership questioned by the repeated invasion of medical procedures, issues of control, transformation, normal, abnormal etc. I think these tropes suggest the history of werewolfism really rather well. Sarah Wassan’s special issue of Gothic studies on Medical Gothic 17.1 (2015) is worth looking at for a lively perspective on the gothic nature of illness. We have to accept that YA fiction functions around metaphor but I agree that this should not be without ambiguity or contradiction, and it should not close down other readings (so I agree with you there).