Goblin mode

Sam George, University of Hertfordshire

“Goblin mode” is taking the current pandemic-ridden world by storm. This state of being is defined by behaviours that feel reminiscent of deep lockdown days – never getting out of bed, never changing into real clothes, grazing from tins or packets instead of cooking, binge watching television and doom-scrolling.

Goblin mode appears to be a reaction to the early pandemic emphasis on home and personal improvement – a “devil may care” attitude in the face of hyper-curated social media content. But this behaviour does not quite align with the goblins of folklore, who take a more playful and mischievous approach to life.

British writer and folklorist Katharine Briggs’s Dictionary of Fairies informs us that goblin is a “general name for evil and malicious spirits, usually small and grotesque in appearance”. Interestingly, the word goblin evolved to refer to a subterranean species – not far off from those who languish indoors during lockdown. But that’s where the similarities end.

There are many variants of goblin, with different characteristics, from the Highland fuath to the English goblin and the French gobelin. Today, the term goblin encompasses any fairy with an injurious intent, such as Knockers, Phookas, Spriggans, Trolls or Trows.

Goblin behaviour can range from mild pranks to acts of outright terror. A goblin is seldom welcomed, even by its own kind. Goblins are certainly a menace in the home. According to mythology expert Theresa Bane, “a house goblin, will work against the family living there, making their life more difficult by banging on pots and pans, knocking on doors and walls and rearranging items in the house”.

In British and German lore, they can shapeshift, and will typically take the form of whatever animal best reflects their beastlike nature. This aspect of goblin lore is represented in Christina Rossetti’s 1862 poem Goblin Market:

One had a cat’s face, one whisked a tail, one tramped at a rat’s pace, one crawled like a snail. One like a wombat prowled obtuse and furry, one like a ratel tumbled hurry skurry.

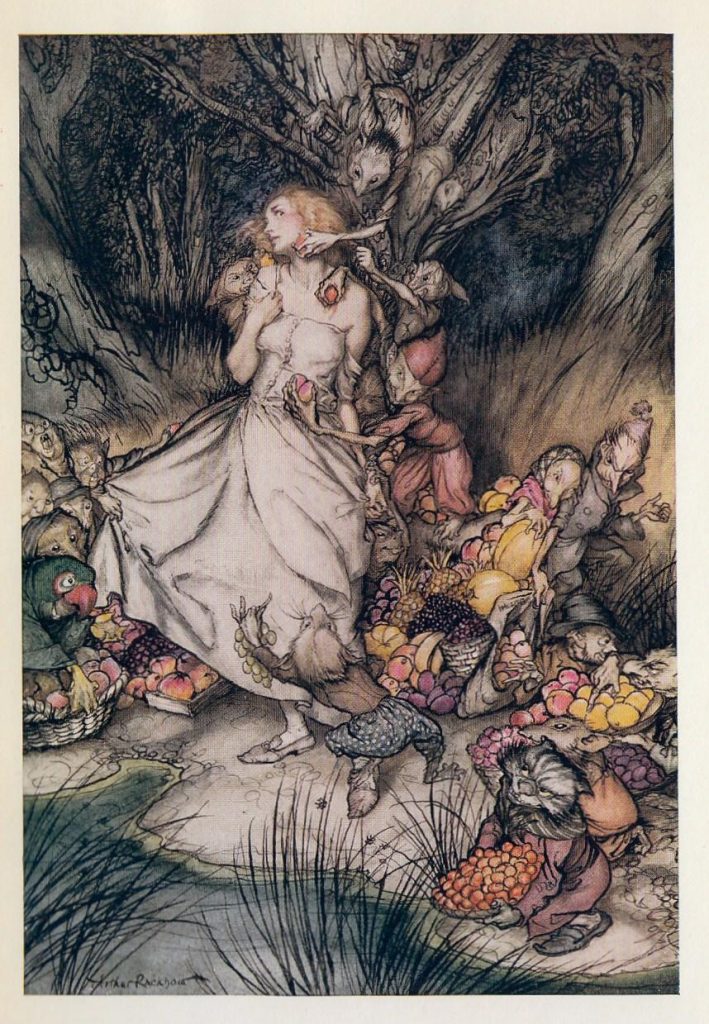

This Victorian poem is an early example of goblins behaving badly. They stand in for predatory corrupting males, using forbidden faerie fruits to lure female victims to their doom. Most goblins depicted in literature and folklore are active, playing pranks and generally causing trouble for the humans around them. They do not sit passively at home, surrounded by creature comforts, lazing the day away.

The “goblin mode” trend might even be seen to malign certain goblins. Hobgoblins, for example, are helpful and well-disposed towards humankind, if sometimes mischievous and tricksy. Puck in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is one such character. Like all hobgoblins, he’s a shapeshifter, and also performs labours for humans, much like the brownie, a house spirit known for its helpfulness.

Vampire mode

A closer look at the goblins of folklore tells us that goblin mode might be somewhat of a misnomer. There is, however, another mythical creature whose characteristics are more fitting for this time period – the vampire.

Vampires have long been associated with disease and contagion. This characterisation draws in part from Dracula, but it also feeds on wider fears and collective obsessions around networks of contagion and contamination.

The 1922 film Nosferatu came out shortly after the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918-19, which killed more people worldwide than the first world war. The word Nosferatu is similar to the Greek word nosforos, meaning “plague bearer”. He even looks like a plague rat, with fangs set at the front of his mouth like the vermin he brings in his wake.

But over the last 200 years, Vampires in popular culture have evolved from plague-ridden creatures like Nosferatu to sparkling, aspirational sex symbols. Instead of holing up and resigning to a fate forever in goblin mode, we should follow the example set by vampires and aim to emerge from the pandemic as better versions of ourselves.

The Cullen family from the book and movie franchise Twilight is the best representation of this dramatic shift. They are attractive, cool, youthful and partake in normal human social behaviour like going to school and dating – a far cry from plague-bearing, sickly Nosferatu. Repulsion cedes to attraction as horror gives way to romance. Goblins by comparison, are unlikely romantic leads, they’re not sexy – or aspirational.

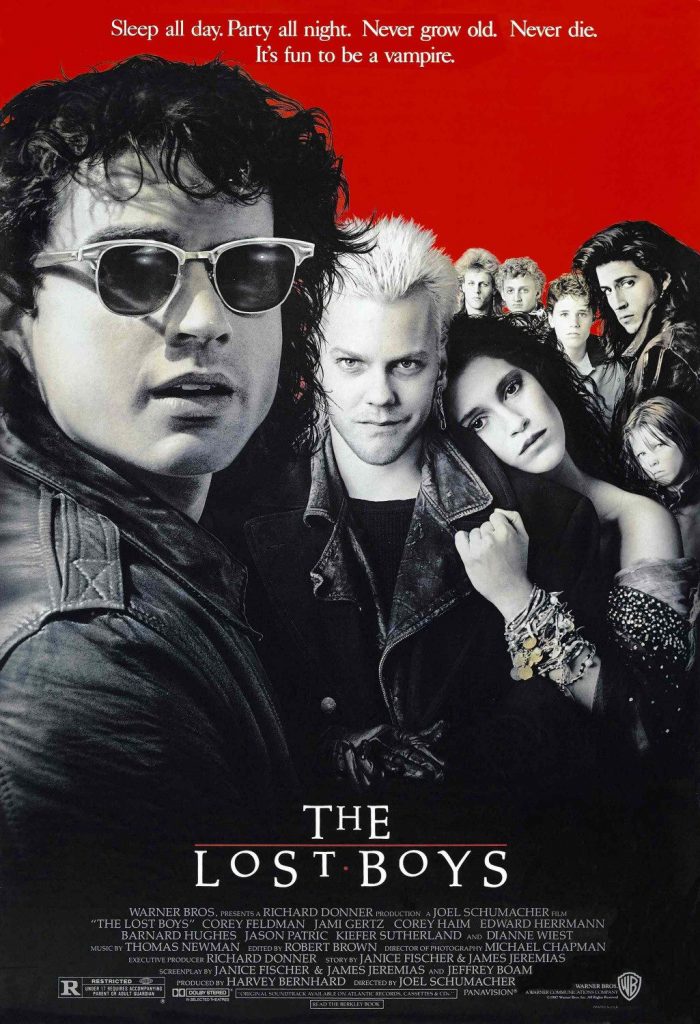

Modern vampires also have an association with youthful culture that could be refreshing after two years of pandemic-induced hibernation. The film Lost Boys, in which Kiefer Sutherland’s undead crew inhabits a fashionably grungy underground domain, was released with the strapline “Sleep all day. Party all night. Never grow old. Never die”. This would be an appropriate post-lockdown motto. It’s time we stopped languishing like goblins and started flourishing as newly born vampires.

Sam George, Associate Professor of Research, University of Hertfordshire

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.