When I found myself in Ireland over Easter I headed to the Dublin Writer’s Museum to look for material on Bram Stoker. The museum presents ‘the literary heritage left by writers of the past’ and it was established ‘to promote interest, through its collections and displays, in Irish literature and the lives and works of Irish writers’. Stoker was in the room which explores the roots of Irish poetry and celebrates story telling and as I hurried excitedly in I was not prepared for what I found. Stoker is far from celebrated here in fact he seems a little bit of an embarrassment. He is perceived as a sensation writer whose novel Dracula is ‘derived from an earlier story called Carmilla by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’. Whilst the two stories are often compared I had never thought of Dracula as derivative in this way and found the museum’s statement puzzling. Elsewhere images of Yeats, Joyce, Shaw etc. are boldly emblazoned on items in the museum shop but there are no signs of Stoker or his world famous vampire.

As I continued around the exhibits it became clear that writers such as Stoker and Wilde are not considered quite Irish enough to fully be embraced. Stoker felt most at home in the English theatre as stage manager of the Lyceum and Wilde established himself in London society at the forefront of the aesthetic movement. The museum informs us that ‘unlike his fellow countrymen Wilde never took Ireland as his subject and for that reason is usually classed as an English writer’. Ironically, Yeats noted that it was Wilde’s Irishness which made English society a foreign country to him. He introduced himself to it as a subversive element.

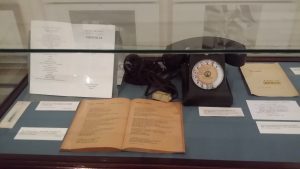

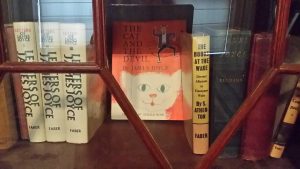

I pondered this as I continued on my tour and came across some delightful oddities such as the telephone Beckett used in his Paris apartment (which blocked in coming calls) and a wonderful first edition of Joyce with a comic devil.

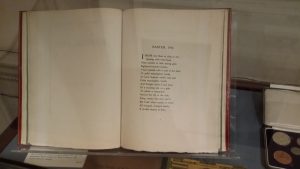

It was hard not to be moved by Yeats whose work was open on the page which displayed the stirring ‘Easter 1916’. Outside there were tour buses visiting the flash points of the rebellion for the centenary. I wondered what Yeats would make of the proceedings and marvelled at the brilliance and futurity of his poem.

Yeats is a persuasive political poet and elsewhere his excursions into the world of fairy have always intrigued me. I may not have found vampires but I did uncover Joyce’s devil and left with a very fine copy of The Book of Fairy and Folk Tales of Ireland edited by Yeats. This contains several specimens of fairy poetry but Yeats is keen to stress that it is more like the fairy poetry of Scotland than England ‘the personages of English fairy literature are merely, in most cases, mortals beautifully masquerading. Nobody ever believed in such fairies […] nobody ever laid new milk on their door stop for them […] As to my own part in this book, I have tried to make it representative […] of every kind of Irish folk-faith. The reader will perhaps wonder that in all my notes I have not rationalised a single hobgoblin’ (W. B. Yeats, Fairy and Folk Tales of Ireland, p. 8).

I smiled at Yeats’s humour here as an English believer in the fey though it did seem strange that Yeats’s fairies are given such prominence in the museum whereas Stoker and his vampire are marginalised – a thing of darkness unacknowledged ‘mine’. Stoker represents the darkness in the Irish imagination whereas Yeats is full of wonder and awe. Both turn to folklore but for Stoker it was Gerard’s Transylvania that shaped his vampire and not the Irish folktales of Yeats’s storytellers. There is a common theme in Irish literature of entrapment, retreat and revolt however and this can be seen even in Yeats’s visionary melancholy and descriptions of the fey.

Where dips the rocky highland/Of Sleuth Wood in the lake,/There lies a leafy island/ Where flapping heron’s wake/ The drowsy water-rats. /There we’ve hid our fairy vats/Full of berries,/And of reddest stolen cherries./Come away, O, human child!/To the woods and waters wild/With a fairy hand in hand,/For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand.

(From W, B. Yeats, ‘The Stolen Child’)

Despite the elusive Dracula and the museum’s stance on Stoker I very much enjoyed the experience of being in a museum for writers and 18 Parnell Square is a beautiful Georgian townhouse bursting with paintings, books, artefacts and manuscripts of all kinds. It also houses the Gorham Library which is the work of the architect Michael Stapleton, one of Dublin’s finest ‘stuccadores’ (excelling in decorative plasterwork). It is not quite like any other museum I have ever visited and is well worth seeing. I will most definitely return and probe more into the archives and series of events.

This is incredibly interesting. It is also further evidence of how popular literature, especially popular Gothic literature, is derided and ignored by the academy. The complexities of national identity also add a further layer of complication to how literature is appropriated and celebrated. I find the dearth of folklore in England a little sad. I find myself searching for pixies and kelpies and will-o’-the-wisps everywhere.

Yes, there are so many issues here but given that this is a major tourist attraction you would think they would make more of their famous vampire. It does not make sense commercially and shows there is a wider agenda around literary worth and national identity and gothic yes. They love their poets the most and Yeats ticks all the right boxes in terms of Irishness, politics and being a bard. On the subject of British folklore you must get a copy of Briggs ‘British Folktales and Legends’ this is epic in terms of material on British folk history. It will renew your faith in English fairies and monsters because there are lots documented in this book!!

I’ll take your advice and get the Briggs. I love folk history. It upsets me when popular literature is ignored because it is not deemed suitable or an acceptable representation of a nation. We are watching the canon being created.

Pingback: 10+ Most Recommended Things to Do in Ireland » City Travel Hub