St Pancras Old Church has withstood the Industrial Revolution, Victorian improvements, wartime damage and an attack by Satanists in 1985. In 1847 the church was derelict and virtually in ruins until Victorian architects Robert Lewis Roumieu (1814–1877) and Hugh Roumieu Gough (1843–1904) transformed the medieval building. They replaced the original West Tower with a large extension and added the Clock Tower to the south. It underwent further restorations of its ancient building in 1888, and 1925.

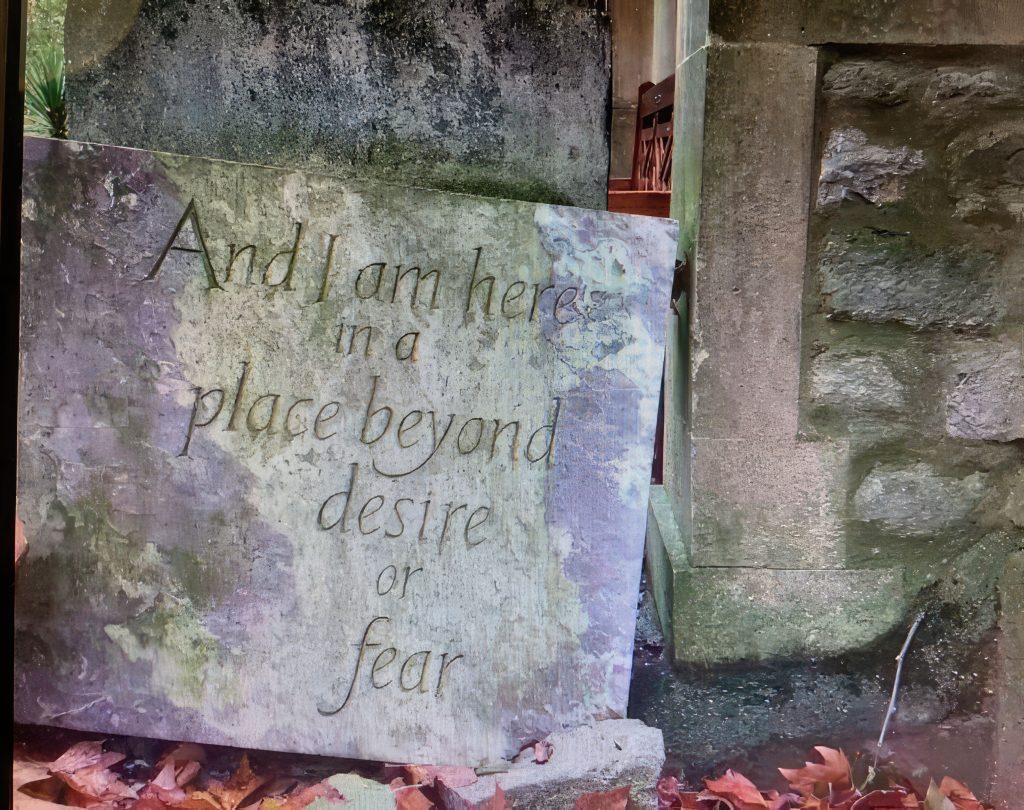

If you enter through the magnificent wrought iron gates, you will find yourself at the entrance to St Pancras Old Church. The high alter, carved panels and old pulpit are ascribed to a pupil of Grinling Gibbons (d.1721). The church appears mostly Victorian Neo-Norman in style. A remarkable memento mori, a reminder of death and the shortness of life can be seen on the Offley family monument which dates back to the 1660s and includes winged angel heads. The winged skull allows visitors to muse on the immortal soul’s flight following its release from the dying body. On leaving the church, if you follow the uncanny path made up of broken headstones, you will find the church’s undead motto, written by Jeremy Clarke, ‘I am here in a place beyond desire or fear’. The motto suggests the transcending of death through visions of new worlds (though this is mysterious and ambiguous). From this you can head into the unsettled Graveyard, John William Polidori’s final resting place.

The churchyard ceased to be used as a graveyard in 1854, by which time it had accommodated centuries of burials. Records indicate that between 1689 and 1854, 88,000 burials took place, over 32,00 in the final 23 years[i]. The picturesque and leafy setting is offset by beautiful gardens surrounding the church which were opened in 1877; the remains of two graveyards, St Pancras and an extension to the churchyard of St Giles in the Fields. Twice in the late 1800s the St Pancras Railway sought to acquire the land. Graves were subsequently disturbed and dismantled and the bodies exhumed. A great many unidentified human fragments were placed in a deep pit and covered over. The architect at this time was Arthur Blomfield (1829–1899) and his assistant was none other than the Victorian novelist Thomas Hardy (1840-1928), then a young man. Many of the disturbed gravestones were stacked under an ancient Ash tree, which has become known as ‘The Hardy Tree’; an uncanny fusion of abandoned gravestones and the roots of a living tree.

The Ash is associated in plant lore with death and resurrection. It has stood serene in divination and in folk medicine from the time of the Norse god Odin. The roots and branches of the Ash Yggdrasil, the mighty world tree of Scandinavian mythology, united heaven, earth and hell. From its wood, after the death of the old gods, a new race would arise.[1] The Ash tree in England has gothic credentials; folklore has it that a failed crop of Ash seeds or ‘keys’ portends a death within a year.[2] In Gothic circles it has become associated with witchcraft, hauntings and demonic curses, due to M.R. James’sghost story ‘The Ash Tree’(1904). [3]

The unsettled, darkly beautiful Ash tree at St Pancras, has fascinated artists and writers down the years. What is remarkable is that John William Polidori’s tomb is rumoured to be one of many unsettled graves under this uncanny tree. ‘Poor Polidori’ uncelebrated in life, and unmemorialised in death, lies somewhere here in an unmarked grave. His death at 25 is often treated as suicide, but the coroner’s verdict of death ‘by visitation of God’ allowed a churchyard burial to take place (suicides were still being buried at crossroads as late as 1823).[4] Musing on Murgoci’s study of the folkloric vampire, where dying unmarried, dying unforgiven by one’s parents, dying a suicide, or a murder victim, can lead to a person returning as a vampire, I can’t help but wonder if Polidori himself, in an act of revenge, his grave disturbed, could have returned a revenant to wander here? [5] Speculation on Polidori’s afterlife dates back to William Michael Rossetti, who recorded his contact with Polidori’s spirit in his seance diary of 25 November 1865.[6]

The church’s theme of bloodsucking and mystery can be traced back to William Blake, another writer who has associations with this place. He placed the site of St Pancras Old Church at the centre of his mystical map of London. ‘The Ghost of a Flea’, a miniature painting by Blake, is an image of vampirism; the flea holds a cup for blood drinking and stares eagerly towards it. Surprisingly, it was produced in 1819 – 20 the very same year as Polidori’s Vampyre.

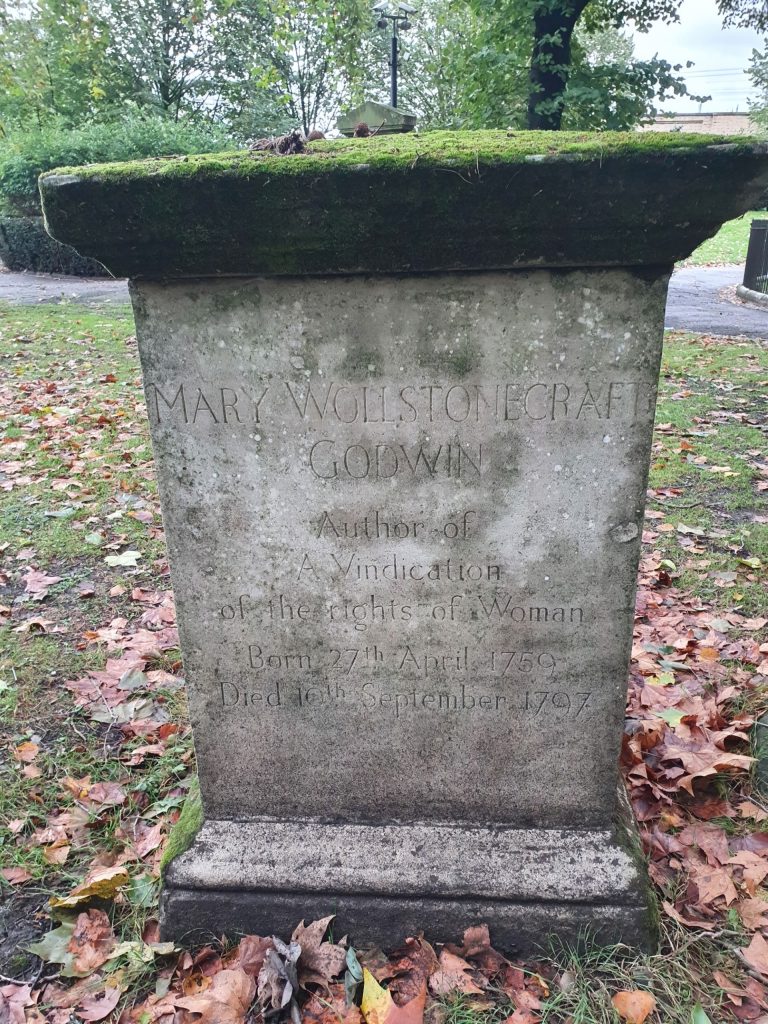

Sadly, the tomb that has inspired the most gothic tourism at the church is not Polidori’s (which is forgotten); it belongs instead to Mary Wollstonecraft. Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, published 1792, died on 10th September 1797, just ten days after giving birth to her daughter, Mary Shelley, who went on to write Frankenstein. The poet Shelley was drawn to the teenage Mary due to her melancholy habit of reading on her mother’s grave. The graveyard was the scene of their courtship and Mary is rumoured to have succumbed to Shelley, an advocate of free love, in this very spot.

The monument can still be seen but the remains of Mary’s parents, Godwin and Wollstonecraft, are no longer buried here, with the disruption of the railway the family removed them to Bournemouth.[7] The Gothic history of the church had only just begun, however; Dickens set his body snatching scene in A Tale Of Two Cities in this churchyard and even today there is a story involving John Tweed, the newly installed vicar at St Pancras Old Church, which is set in the graveyard and features the Hardy Tree, the site of Polidori’s grave.[8] In this fictional account set in 1901, Tweed writes to his wife Charlotte complaining that

‘Every thief, vagabond and ne’er-do-well in London seems to have wound up buried at St P. Which would be all well and good, except that the digging up of late seems to have unearthed more than just bones. Judging by the number of lost souls drifting about the place in one spirit form or another, I would offer that many of my guests are far from welcome in Heaven’.[9]

The Ash Tree is again the focus of Tweed’s letter of December,1859:

‘More missing headstones. Increasingly certain of connection with my guests. Today I traced strange lines of disturbed earth across the graveyard. Each lead to the ash tree. Are they being dragged there? And then where? The Ash tree itself is looking increasingly unhealthy, possibly diseased. I don’t like to get too close to it.’

‘If I hadn’t seen such as I have seen these past months, I may not have trusted my eyes, but trust them I must. I shall record it in as plain a manner as I know how: By the light of the moon last night, I saw a gravestone, moving with some speed, and quite of its own accord, across the graveyard. It hurtled towards the ash tree, at the base of which it disappeared, as if plunging into the very bowels of the tree.’

The Ash tree it seems had become a portal for the restless dead, a veritable hell mouth!! Tweed’s descendants are driven to bury a large bible within the roots of the disturbed tree in an attempt to stave off its demonic curse.

This same tree, the St Pancras Ash tree, The Hardy Tree, holds the secret to Polidori’s grave. In December 2022, just over two hundred years after his burial, it collapsed suddenly in a storm, the stacked gravestones remained entirely intact.[10] As for St Pancras Old Church, and its history, well it’s hard to out goth that!!

With thanks to Father James Elston. Photos: Sam George

This article is extracted from Sam George’s Afterword to The Legacy of John Polidori: The Romantic Vampire and Its Progeny, ed. by Sam George and Bill Hughes, MUP, 2024

Sam is completing an AHRC funded project on ‘Gothic Tourism: John William Polidori and St Pancras Old Church’. She is developing a Polidori Tour. If you are interested in joining, please email s.george [@] herts.ac.uk for dates and info.

[1] The mighty Ash tree Yggdrasil is discussed widely in Neil Gaiman’s Norse Mythology (London: Bloomsbury, 2017), pp. 23-31.

[2] It is reported that no Ash tree in England bore ‘keys’ in 1648, the year before the execution of Charles 1st. See Margaret Baker, The Folklore of Plants (Oxford: Shire, 1969), p. 19.

[3] ‘The Ash Tree’ appears in M. R. James’s Ghost Stories of an Antiquary (1904).

[4] See my research on the folklore of crossroads ‘Vampire at the Crossroads’ https://www.opengravesopenminds.com/ogom-research/vampire-at-the-crossroads/ [accessed 07/05/2023]. For Polidori’s death, see Henry R. Viets, ‘‘By the Visitation of God’: The Death of John William Polidori’, British Medical Journal (1961), 1773-75. D. L. Macdonald argues that the jurors had known Polidori at Ampleforth School and that the coroner acted out of sympathy for the family, Poor Polidori: A Critical Biography of the Author of The Vampyre (Toronto, Buffalo and London: University of Toronto Press, 1991), p. 237.

[5] Agnes Murgoci, ‘The Vampire in Roumania’ [sic] Folklore, 86, 320-49.

[6] See D. L. Macdonald, Poor Polidori, pp. 240-41.

[7] Mary Shelley was buried with the remains of Shelley’s heart in St Peter’s Churchyard, Bournemouth. The remains of her parents, William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft were moved to the same plot in 1851 when St Pancras Churchyard was broken up for the railroad. See Sam George, ‘Gothic Hearts: A Love Story’ https://www.opengravesopenminds.com/ogom-research/lost-hearts-a-gothic-love-story/ [accessed 07/05/23].

[8] Anon, ‘Exit Strategy for a Restless Dead: The Hell Tree of St Pancras’ https://portalsoflondon.com/2017/01/20/the-hell-tree-of-st-pancras/ [accessed 07/05/23]. All further references are to this source.

[9] Anon, ‘Exit Strategy for a Restless Dead: The Hell Tree of St Pancras’.

[10] See John Sutherland and Kevin Rawlinson, ‘The Historic Hardy Tree falls in London’ The Guardian, 27, December, 2022 https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/dec/27/historic-hardy-tree-falls-in-london [accessed 07/05/2]3

[i] See A Walk in the Past (London: St Pancras Old Church, n.date), p. 4